Last night I tuned in to one of my favorite NPR programs, Ira Glass' This American Life, which, if you're not familiar with it, is a collection of brilliantly composed vignettes highlighting bizzare, funny, poignant, often ironic aspects of life, told in true documentary fashion, where the storyteller never gets in the way of the subject. The third act of this episode, originally broadcast January 18, focused on the experience of workers in FAO Schwarz's marketing scheme to sell high-end dolls, its "Newborn Nursery Adoption Center."

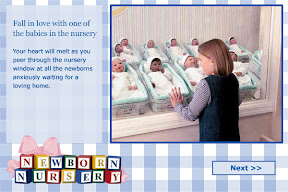

Last night I tuned in to one of my favorite NPR programs, Ira Glass' This American Life, which, if you're not familiar with it, is a collection of brilliantly composed vignettes highlighting bizzare, funny, poignant, often ironic aspects of life, told in true documentary fashion, where the storyteller never gets in the way of the subject. The third act of this episode, originally broadcast January 18, focused on the experience of workers in FAO Schwarz's marketing scheme to sell high-end dolls, its "Newborn Nursery Adoption Center."From the doll manufacturer's website:

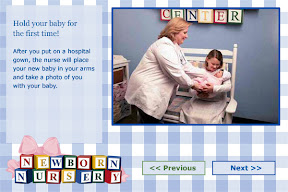

Twenty combinations of hair and eye color are available for adoptive parents to choose from, followed by the completion of the adoption application and choosing the baby's name. The doll arrives wrapped in a blanket and is then placed in the arm of the waiting mother. The center's "staff nurse" takes a photo of the mother and child, then receives an official adoption certificate, complete with footprint. Accessories for baby, including hats, booties and blankets, are for sale around the adoption center.

Ostensibly a story about prejudice toward racial minorities and people with disabilities with only a slight nod toward the adoption industry's commidification of children (a supervisor instructs staff never to mention the word"sell" in its "adoption interview" before it collects the "adoption fee"), the storyteller, in this case a sales associate ("nurse") recounts her experience of customer reactions when all the white babies sell out, leaving row upon row of minority babies lying unadopted in their "incubators."

Where to begin?

- the obvious racism of customer's "adoptive" preferences?

- the stereotypically gendered scripting of adoptive "little mommies?"

- the callously accurate representation of the wholesale commodification of adoptees?

- how about the normalization of generation falsified birth certificates?

- how about the fact that the "babies" retail for over $100 (my one year old has a lovely baby doll we got for around nine bucks)?

Now this stuff is probably old hat to most of you readers, but being that I'm an old school Vermont hippie, a bit out of touch with the wonders of American mass marketing, I hope you'll forgive my naivete. Can it really be that after all these years that nowhere in the chain of marketing command at either the doll manufacturer or retailer there was no one with a basic understanding of what's wrong adoption? *sigh*